Poland in World War II — An Overview

Prelude

From March 1936 to March 1939, Germany under Nazi leader Adolf Hitler occupied, without any opposition, the demilitarized Rhineland bordering France, the entire country of Austria, the Sudetenland in northwest Czechoslovakia, Memelland in Lithuania, the remainder of Czech lands, and was threatening to seize the Baltic port of Danzig in northern Poland. At that point, Britain and France pledged to support Poland should Germany invade.

The spring and summer of 1939 were filled with tense negotiations among Germany, Britain, France and Poland, last minute attempts to stave off war. Unlike Austria and the other lands that had rolled over for Hitler, Poland refused to concede — and became the first Western Ally to fight the German war machine.

WWII Begins

Blitzkrieg — Adolf Hitler’s “lightning war” — was born September 1, 1939 with the German invasion of Poland. Two days later, on September 3, 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany, but failed to take any military action.

On September 17, 1939, Joseph Stalin’s Soviet armies smashed through Poland’s eastern border. Trapped between two rapacious enemies, Poland’s fate was sealed.

Within a month, Poland fell. By June 1940, France, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Norway had all followed, and Britain was fighting for its life.

Although occupied by two hostile enemies, Poland continued to fight both abroad and at home.

In the West

At the end of September 1939, most of the Polish Air Force, and part of its army and navy, were able to make their way to France. The Polish forces fought with the French against the Germans — and then when France surrendered after just 6 weeks, scrambled to escape yet again, this time to Britain.

These Polish forces continued to fight with the Allies throughout the entire war, on every front — including the Polish fighter pilots who were instrumental in helping to save Britain during the most desperate hours of the Battle of Britain in the summer and fall of 1940, the Polish Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade which fought at Tobruk, and the Polish tank divisions at Normandy that won the hard-fought Battle of Falaise.

For the most crucial year of the war, from June 1940 when France surrendered to June 1941 when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Poland was Britain’s largest ally.

Under German Occupation

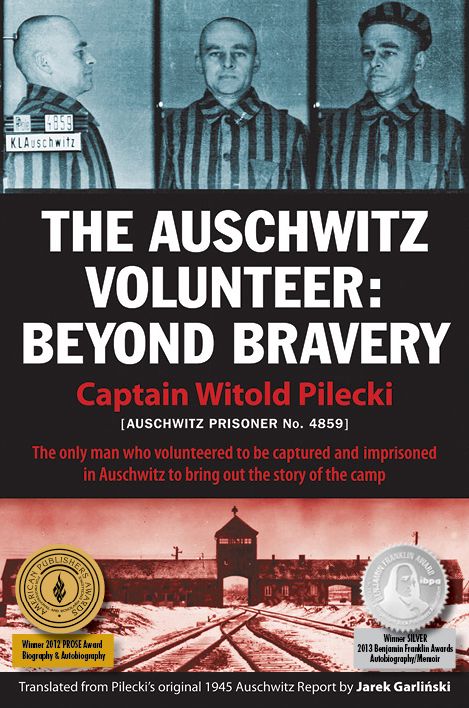

In German-occupied western Poland, an entire clandestine civil government (with courts, education, health, legislative and other usual government functions) and military organization (the “AK,”Armia Krajowa [Home Army or Army of the Homeland]) formed underground, under the very noses of the brutal Nazi occupiers, taking their orders from the Polish government-in-exile in London via perilous courier networks and risky radio transmissions. The Polish Underground State was the largest non-communist resistance organization in occupied Europe.

The underground government and AK operated with very few resources, against insurmountable odds and the threat of unspeakable tortures and killings, with an average personal life expectancy of three to four months…yet there was never a lack of volunteers, including women and young Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

At its height, the AK numbered approximately 300,000 underground soldiers, in cities and forests, engaged in sabotage and intelligence gathering. Among them was a small hand-picked group of Polish soldiers and airmen who had been trained in Britain as elite Special Forces called cichociemni (the unseen and silent, or silent and shadowy ones), and parachuted back into Poland to work with the underground resistance.

The Nazis’ persecution of Jews is well known. Approximately 3 million Polish Jews, representing about 90% of the prewar Jewish population of Poland, were killed in Nazi concentration camps, in the sealed Ghettos established by the Nazis in Warsaw and other cities, and in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943.

But the Nazi terror in occupied Poland was not limited to Polish Jews — an estimated three million or more Christian civilians in Poland were also killed in Nazi concentration camps, in arbitrary round-ups on city streets and in buildings, and in operations including the Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

Soviet Occupation & Siberian Deportations

In the east, meanwhile, the Soviets captured approximately 200,000 Polish soldiers during the September 1939 campaign and sent them to Siberian POW labor camps. In what has become known as the Katyń Massacres, the Soviets executed approximately 8,000 Polish officers, together with another estimated 14,000 Polish intellectuals, professionals, policemen and other Polish civilian leaders, and buried them in mass graves in the Katyń Forest and elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

Beginning in February 1940, the Soviets also forcibly deported hundreds of thousands (some estimates range as high as 1.5 million) Polish civilians — entire families arbitrarily designated as “enemies of the people” — to Siberian slave labor camps. According to some estimates, as many as 50% of these deportees died under the harsh conditions.

The Polish II Corps

In June 1941, Hitler turned on his erstwhile ally Stalin when German and Axis forces invaded the Soviet-occupied territories of Eastern Europe and rapidly advanced into the Soviet Union. As part of the price for joining the Western Allies, Stalin had to free those Poles who still survived and agree to the formation of a Polish army on Soviet soil.

Polish General Władysław Anders, who was himself released by the Soviets from the Lubyanka Prison, was given the task of forming this new Polish army. Accepting all the freed Poles (men, women and children) who could find their way to the new army, Anders got them out of the Soviet Union, to Iran, Iraq and Palestine where they trained with the British. Often called “Anders Army,” this force became the nucleus of the Polish II Corps – the soldiers who finally took Monte Cassino after three failed attempts by American, French, and British and Commonwealth units, thereby opening the road to Rome for the Allies.

Concluding…

The Polish experience in WWII was probably the most complex, far-flung, heroic and tragic of all the Western Allies — and yet is the least known.

This summary touches on only a few key aspects of this incredible history whose ramifications echo into modern times. You’ll find more a in-depth look at various aspects in our titles.

Download a pdf of this brief summary of Poland in WWII.