USHMM celebrates Captain Witold Pilecki and The Auschwitz Volunteer

USHMM celebrates Captain Witold Pilecki and The Auschwitz Volunteer

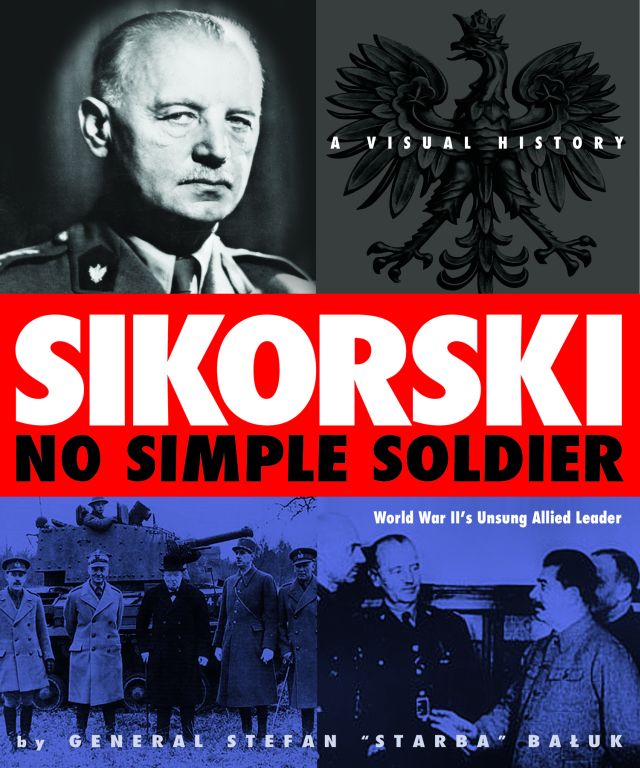

Coming Fall 2024 Sikorski: No Simple Soldier—A Visual History of World War II's Unsung Allied Leader

Coming Fall 2024 Sikorski: No Simple Soldier—A Visual History of World War II's Unsung Allied Leader

![]() 2023 Aquila Polonica Article Prize WInner Announced

2023 Aquila Polonica Article Prize WInner Announced

![]()

Aquila Polonica on national TV - interview on Lifetime television morning show The Balancing Act

![]()

Wall Street Journal Europe – Opinion by Aquila Polonica publisher Terry Tegnazian, “Polish Heroes: The history of the country's World War II resistance against Nazi Germany fell victim to Realpolitik.”![]() Publishers Weekly – “Aquila Polonica Finds Its Niche”

Publishers Weekly – “Aquila Polonica Finds Its Niche”![]()

Warsaw Business Journal - Opinion by Aquila Polonica publisher Terry Tegnazian, "The Polish Connection."

TELL A FRIEND

MAILING LIST

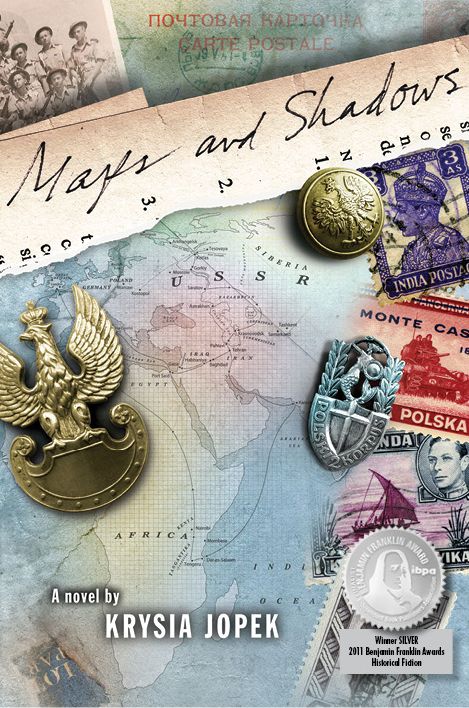

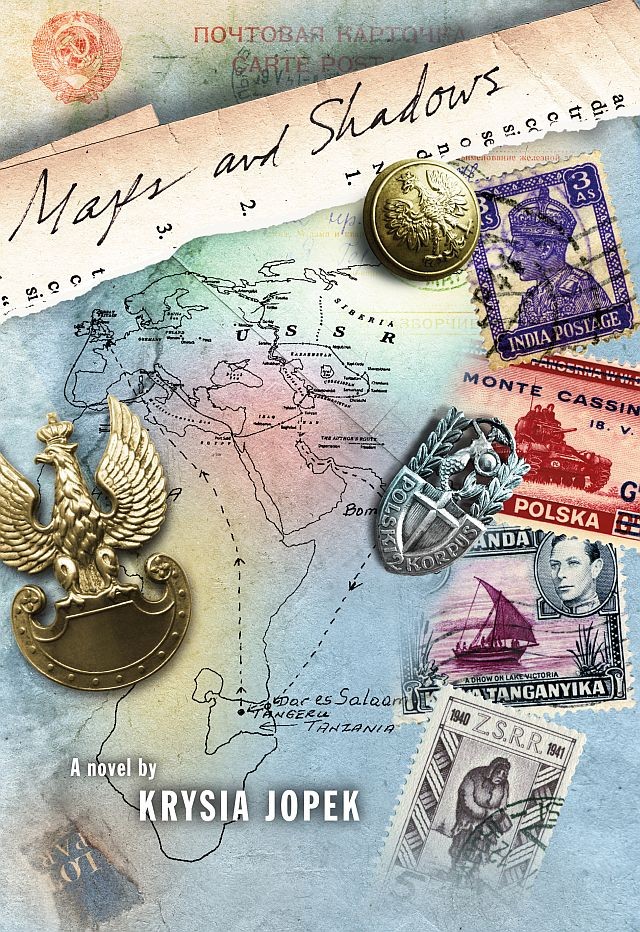

Maps and Shadows

Maps and Shadows

About the Author

KRYSIA JOPEK received her B.A. and M.A. in English from the University of Connecticut, her M.Phil. in English from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center, and her M.F.A in Literary Fiction from Albertus Magnus. She studied in London, England for a year, and taught English literature and writing at City College of New York for ten years, and subsequently taught English at Westfield State University.

KRYSIA JOPEK received her B.A. and M.A. in English from the University of Connecticut, her M.Phil. in English from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center, and her M.F.A in Literary Fiction from Albertus Magnus. She studied in London, England for a year, and taught English literature and writing at City College of New York for ten years, and subsequently taught English at Westfield State University.

She has published poems in various literary journals, including Crisis Chronicles, Split Rock Review, The Woven Tale Press, Great American Literary Magazine, Gone Lawn 19, Columbia Poetry Review, Windhover, Prairie Schooner, The Wallace Stevens Journal, Phoebe, Murmur, Prometheus, and Artists & Influence, and her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She has also published reviews of poetry in The American Book Review, and a review of literary criticism in The Wallace Stevens Journal.

Maps and Shadows is her first novel. Jopek based her story on the history of her own family, as well as extensive independent research. She brings her rich literary and poetic background, and a worldview of global dimension, to illuminate this lost piece of history with lyricism and grace.

She resides in Connecticut in her Poet’s Cottage with T.S. Eliot (Eliot for short), an amazing rescue dog from Houston, Texas. You can follow her on facebook on her personal page, Krysia Jopek Author Page, or Benson Jopek’s fan page (T.S. Eliot’s page taken over by former rescue dog, Benson Jopek). Please check out her website: www.krysiajopek.com and keep your eyes open for the upcoming publications of The Glass House of Forgetting and The Island Within.

The cartographer, busy rearranging borders,

does not hear the gunshots, glimpse the people...

Buy the Book!

WINNER of the SILVER AWARD

for HISTORICAL FICTION

at the 2011 Benjamin Franklin Awards

Maps and Shadows

A Novel

by Krysia Jopek

Four voices. Four lives. Four paths.

One family.

Vivacious Helcia, fifteen years old, with flowing molasses-colored hair, loves poetry and history.

Cocky Henryk, at twelve, is already testing the limits of manhood.

Their father, Andrzej, veteran of an earlier war to defend their Polish homeland, proudly built the family farm from the ground up.

Zofia, their mother, sings as she works in the home she loves, gazing out the kitchen window to admire their land, their crops, their thriving children.

February 1940

A pounding Russian fist on the door in the middle of the night—and they will never see their land again.

Swept into a World War II odyssey that spans the map from Poland to Siberia, on divergent paths to Persia, Palestine and Italy, to Uzbekistan and Africa, converging in England and finally settling in America, the family endures…and ultimately triumphs.

This stunning debut novel from poet Krysia Jopek takes a fresh stylistic approach to storytelling, fusing a minimalist narrative with lush lyricism.

Jopek draws on a little known chapter of World War II—the Soviet deportations of 1.5 million innocent Polish civilians to forced labor camps in Siberia shortly after the Soviets occupied eastern Poland at the beginning of the war. Beautifully written, lyrical and poetic, Maps and Shadows explores the impacts of this shattering experience on the family from four points of view.

Slowly the threads are woven together—the father’s secret shame at not being able to protect his family; the son’s need to grow up quickly; the daughter’s descent into nightmares, seeking comfort in broken bits of poetry consigned to scraps torn from a precious salvaged dictionary; the mother’s instant aging, her hidden fears and worry.

World War II was perhaps the most transformative event of the twentieth century. Maps and Shadows illuminates a lost piece of this history, while addressing themes of displacement, loss, resilience and, ultimately, new beginnings in a new land—experiences familiar to a vast number of contemporary readers.

"Haunting...well-researched...recommended to those

who like their historical fiction autobiographical and real."

— Historical Novels Review

"Jopek...shows how very talented she is...I definitely

recommend this book on several levels,

especially for the writing."

— Nightreader

DETAILS:

MAPS AND SHADOWS: A NOVEL

- Pub Date: December 2010

- Hardcover ISBN 978-1-60772-007-2

Cover price $19.95

- Trade paperback ISBN 978-1-60772-008-9

Cover price $14.95

- Ebook ISBN 978-1-60772-013-3

Price $9.99

- Author: Krysia Jopek

- Language: English

- Pages: 160

- Size: 6” x 9”

- 12 black & white illustrations; 8 original poems

- Publisher: Aquila Polonica Publishing

MAPS AND SHADOWS - EXCERPT

MAPS AND SHADOWS - EXCERPT

CHAPTER 2

The Cattle Train (Helcia)

The Russian soldiers packed us forcefully into the fifty empty cattle cars that were waiting for us at the train station. In total, as a result of three separate evacuation phases, 1.5 million Poles from the eastern portion of our country were deported like us, forced on command to leave our home and what could not be carried, or be killed.

The soldiers pushed approximately sixty of us into each cattle car, which had two wooden shelves on each side, ten people to a shelf. Their guns nudged us; they were especially rough with the men. You think you’re tough, you think you’re a soldier? You have no uniform now.

There was a subtle undercurrent of insecurity, however; perhaps they realized that it was in some way arbitrary, that they were wearing the uniforms and not Tata and the other Polish veterans. On another day, the tides could turn—a queen removed quickly from the game of chess with one bullet, with one official document signed, one mass grave that would be vehemently denied. But I shall adhere to the facts for now.

There was a small, wood-burning stove in the middle of our cattle car, but no toilet facilities. One man cut a round hole in the floor with a hatchet he had brought from his farm. Someone else draped a blanket around the opening and that became our latrine for the unknown number of days ahead of us. We had no idea how long our journey would last, if we would see “normal” days again. I dreaded using this mock-toilet, but then the pain attacked and doubled me over, forcing me to confront the smell, the unsanitary conditions, and the degrading feeling of being reduced to an animal—while trying to stay balanced and not vomit the minimal contents in my stomach, as the dirty, portable barn jerked on the tracks.

We were incredibly hungry and found it difficult not to think of food, not to imagine what we would be eating at each meal, if we were home. I could smell fresh meat cooking in my memories and struggled not to salivate and not to cry. Aside from the cold scraps of fish or barley soup and slice of dark, waterlogged bread that we received every two or three days from the Russian soldiers, we subsisted on the food we brought from home—kasha, various grains, dried meats. We didn’t know how long the food supply from our farm would last. It seemed strange that they were feeding us periodically, keeping us alive. I kept thinking we were being saved to be tortured or to be worked to our bones (a psychological and physical ossification), behind the scenes of war, implicated unwillingly. But at least we were alive, unlike other village family members. Many fathers of children my age and younger had mysteriously disappeared, those who were still active in the military and of significant rank. The Russians claimed that they must have fled, but there were no traces of any such conjectured journeys.

Hour after hour, unrelenting day after day, the clunking of the steel tracks droned, clacked, and droned. We were not informed of our destination but we could guess, given the order to pack warm clothes. Siberia, the northern place of historical exile depicted in nineteenth-century oil paintings that I had read about in school. The place of political eviction for fugitives, dangerous individuals and so-called “undesirables.” Or in our case, an inconveniently located group of people with strong military affiliations. And I was the oldest, the ancillary mother of Henryk and Józef—in case anything happened to Mama—in case we were separated from the adults. In case we were lost.

The train stopped every forty-eight hours or so, usually to pick up more coal for the two locomotives that were pulling and pushing the storage cargo of three thousand Poles. Immediately, as the train halted, a throng of restless gray bodies pressed against the door of the cattle car to jump off as soon as possible, to relieve hunger and claustrophobia. Eyes squinted against the sudden sun and the magnitude of the landscape, adjusted and immediately scanned the area for food, hoping for maybe some dried meat or mushrooms, or the vestiges of fish to make soup, speculating whether anything could be traded. The area was also hastily surveyed for a private place to urinate or defecate instead of the semi-public toilet on the train.

The Russian peasant women tasked with sweeping snow from the train tracks met our gazes nervously. They were being watched carefully by Russian soldiers. I noticed their shoes were in poor condition and they were missing teeth. They resembled the grandmothers of some of my schoolmates, a kerchief wrapped over their heads and tied at the chin.

The train was safer than being found as an escaped Russian prisoner. At least we were together.

/////

Excerpt from Maps and Shadows: A Novel, by Krysia Jopek. Published by Aquila Polonica Publishing. Copyright 2010 Krysia Jopek.

Maps and Shadows

Buy the Book

BUY this award-winning book NOW from your favorite online retailers OR at your local bookstore (if they don't have it in stock, they can order it for you). It's currently available in trade paperback and ebook. (For retailers and libraries: our titles are distributed through all major wholesalers and National Book Network—scroll all the way down this page.)

BUY this award-winning book NOW from your favorite online retailers OR at your local bookstore (if they don't have it in stock, they can order it for you). It's currently available in trade paperback and ebook. (For retailers and libraries: our titles are distributed through all major wholesalers and National Book Network—scroll all the way down this page.)

Here are a few online sources:

At an independent bookstore near you

FOR RETAILERS & LIBRARIES:

Aquila Polonica titles are distributed through all major wholesalers and by National Book Network.

Phone (toll free): 1-800-462-6420

FAX (toll free): 1-800-338-4550

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Website: www.nbnbooks.com

For international orders, go to: http://distribution.nbni.co.uk/how-to-buy-from-us/

MAPS AND SHADOWS — EXCERPT

PRELUDE

Angles of Memory (Helcia)

Everyone has a story.

Some stories are difficult to believe, though true. Others accurate, yet dull. Some difficult to tell—apart from the others. One story often spills into another, echoes, diverges before crossing trajectories again. The skeins once separated, can fray. To isolate the variable can unthread the most composed, even the most vain.

This is my story and my younger brother Henryk’s story. My mother Zofia’s and my father Andrzej’s. My youngest brother Józef doesn’t speak of these places. Somehow his memories were lost.

A story of war, shifting boundaries, alliances and ideologies. A story of mid-twentieth-century ice and burning sun.

***

History tells such stories, recorded through speech, shaded recollection. The human hand carves on stone, brushes ink to tablet, lines on a map, throws pottery on a wheel, carries a gun, pats the shoulder of another firmly it will be okay, coaxes the infant to sleep, looks over the shoulder—and up ahead.

These gestures to understand, represent, make the past manageable—to pass the book on. Here is our chapter, remember us. Now what will you do—knowing all this?

Spin the globe blindfolded and point to a country to see if it is still there. Take scissors and cut out the divisions between nations on a map. An exercise in rhetoric and chance.

Ancient themes reemerge: history repeating itself incorrigibly. Tenacious greed. The snake eating its own tail makes a circle, alpha and omega, a process, a spin.

A free country is not free not to go to war.

War, it is said, the path to freedom.

Yes, there are many stories and many ways to tell one story. Manifold shadows of one tree. Though the limbs can be truncated and leaves shorn.

Some need to speak, to tell the others; others cannot bear to remember, relive. They cannot be relieved, afford to recollect, risk a bankruptcy of the worst kind.

One can be born into a line of kings, another the son of a soldier. The daughter of the king could not marry the peasant’s son. The peasant’s son dreams of a marble, the eye of a saint on a stick for public display.

Some are born into a way of worshiping or not worshiping God. To be born on one side of a barbed wire fence or stone wall, identified with a group of people as better, or turned away—you do not belong. You are not one of us. You cannot stay—

If lucky, take your family and leave. If separated from your family, look through the debris. There are agencies to verify. Records of teeth. Fill out the forms properly. We will send a flag even if you cannot speak. Even if there is no longer a country.

There are those who worship power, money, prestige. The ego trying to press itself into the pages of history, unable to admit defeat. I was here x years and this is what is left. Remember me.

One’s character, place, and time: the x, y, and z.

The fields, the skies, and angle of memory.

Some are born without proper shelter, without the luxury of food, safety, academic training, access to employment, ladder mobility. Others born into mansions, many born into disease. So many variables seemingly shaken in a hat— or perhaps pre-mapped, depending on one’s beliefs. Who is to say?

***

This is my family’s story. A story of starvation and betrayal. One chess game of many in the tome of history, yet a complicated game with repercussions nonetheless.

A story of survival for a few—a story of intense cold and heat. A story of mid-twentieth-century ice and burning sun.

A story of maps and shadows.

###

Excerpt from Maps and Shadows: A Novel, by Krysia Jopek. Published by Aquila Polonica Publishing. Copyright 2010 Krysia Jopek.

BOOKS & DVDs

Download Current Catalogue

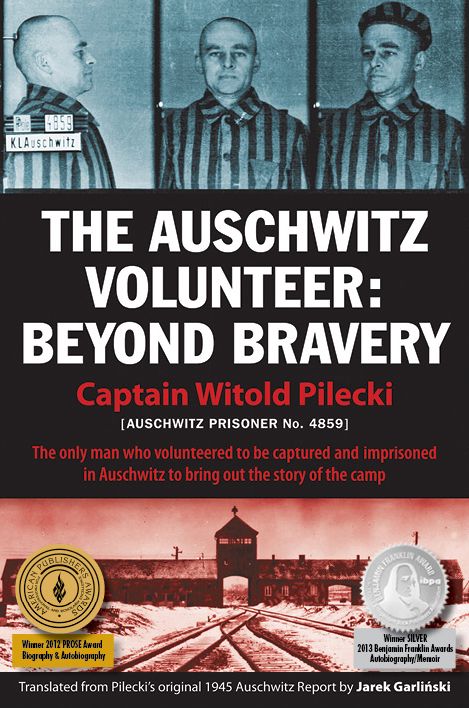

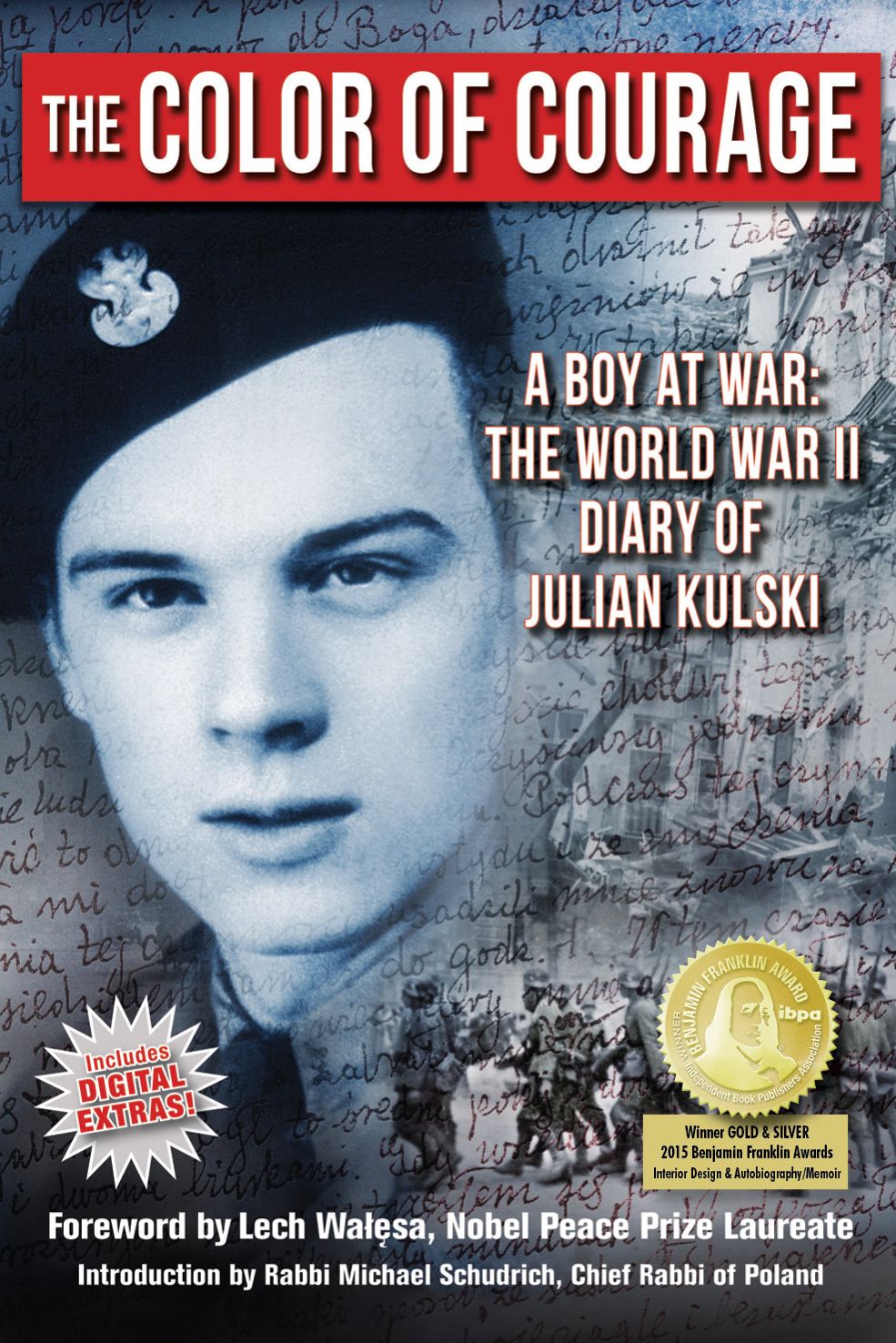

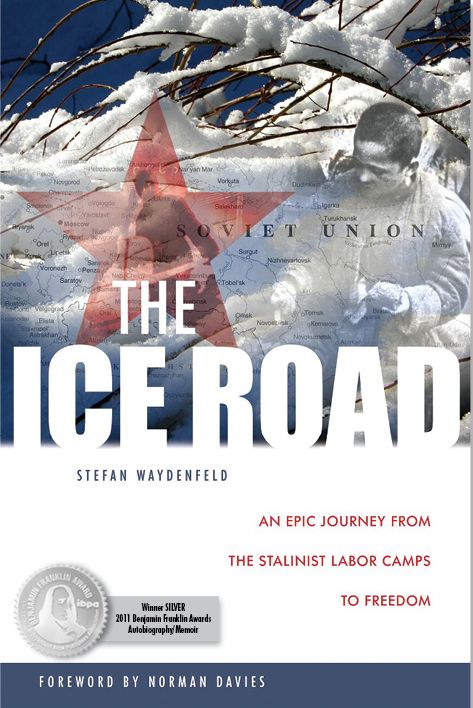

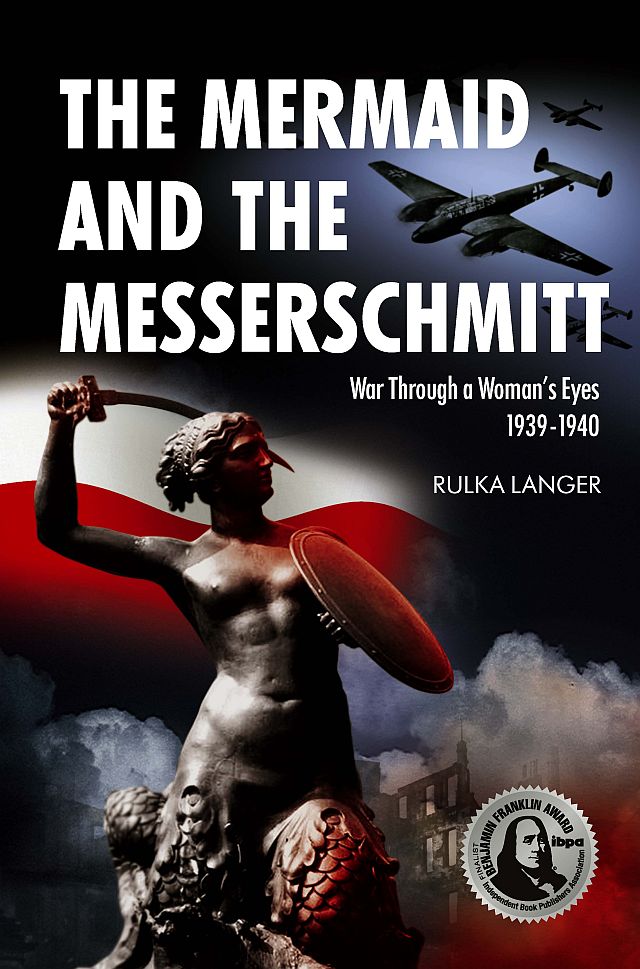

Click on the covers below for more info on each book

Fighting Auschwitz: The Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp

by Józef Garliński

Download Fighting Auschwitz Info Sheet